“Grey Rhinos”: Why Xi Jinping is preparing China for a serious test

It is the tradition of the Chinese Communist Party’s congresses to inspire optimism. Hence the refined formulation over the years that peace and development remain the main content of the era. This has been said from the platforms of Party forums since the days of Deng Xiaoping. But according to Igor Denisov, a senior fellow at MGIMO’s Institute of International Research, the twentieth Communist Party Congress offered a different picture of the world, one that can hardly be called optimistic.

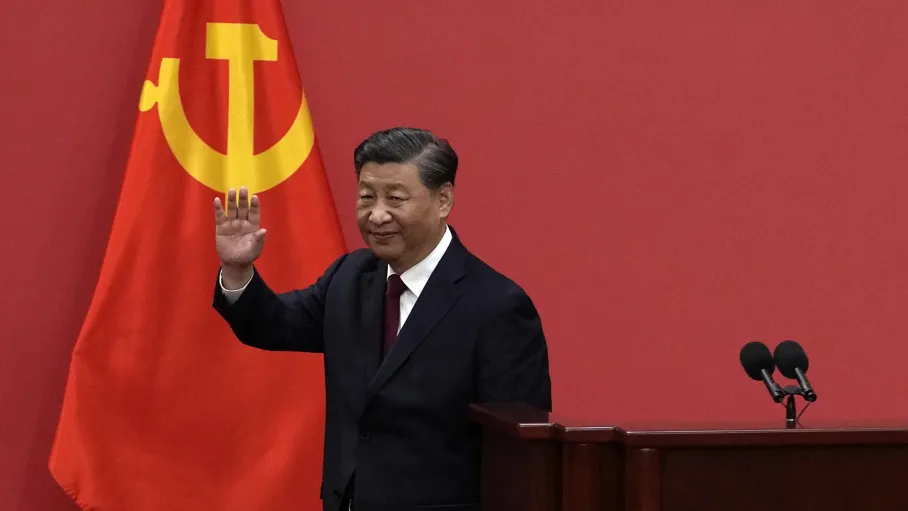

Speaking to Congress delegates, CCP General Secretary Xi Jinping, who was eventually re-elected for a third term, said that the future of humanity is bright only “in the long run. This was reminiscent of something Mao Zedong said in 1945: “We must conduct constant propaganda among the people, telling them about the progress and bright prospects for the world, so as to imbue them with the belief in victory. At the same time, we must also tell the people, tell the comrades, that the road is winding.”

According to current party assessments, the road to a stable peace is potentially possible, but it is not just winding, it is not even very visible yet. The image of bad weather has become a cross-cutting theme in Xi Jinping’s discourse on growing challenges. At one point in the report, he used the Chinese idiom “fix the roof before it rains,” calling for advance preparation for even greater challenges. Concern over global instability was also echoed in Xi’s use of the images of “wind,” “waves,” and “stormy tempest” characteristic of Chinese poetry.

However, the Secretary General also turned to other symbols associated more with modern Western political culture than with Chinese classics. It is not the first time Xi Jinping has used the images of “black swans” and “gray rhinos,” but this is the first time such a warning about geopolitical risks has been uttered from such a high rostrum.

Four problems

The publishers of Nassim Taleb and the American political scientist Michelle Wacker, the author of the “gray rhinoceros” concept, can now put a quote from the Chinese leader’s report to the 20th Congress on the cover. Even before Xi’s Oct. 16 speech, though, Wacker proudly pointed out on her website, “The best-selling book in English in China is the book that shapes China’s planning and policy for the future.

The book in question is Wacker’s “The Gray Rhino: How to Recognize the Obvious Dangers We Ignore and Take Action,” published in the United States in 2016. A Chinese translation was published in 2017, and during the broadcast of the PRC president’s televised greeting for the new year, 2018, analysts catching any signals about Chinese plans and worldviews spotted the book about the gray rhinoceros on a shelf in Xi Jinping’s office. So it is likely that the repeated references to the dangers that no one wants to notice are not an invention of the speechwriters, but wording authored by the head of the Party and state himself.

The story of why this image has gained such appeal in China is worthy of a separate study. In brief, the concept of the “gray rhinoceros” fits well with Xi Jinping’s approach to strategic planning. The logic goes something like this: China is now most closely involved in the world’s problems, the country has become too strong and too visible, resistance to Chinese growth is growing, risks have increased immeasurably, and therefore any potential dangers must be taken seriously, even if they do not seem obvious. This is why the image of the “gray rhinoceros” has been so enthusiastically embraced in Chinese power circles.

The report mentions four negative phenomena troubling China, in fact, four “gray rhinos” – a peace deficit, a development deficit, a security deficit, and a governance deficit. China sees some support in those elements of the “old world order” that have not yet collapsed. Unlike his speech five years ago at the 19th Congress, in which only the United Nations was briefly mentioned, this time Xi Jinping not only assessed in detail the UN’s fundamental role in the modern world order, but also made positive references to the WTO, SCO, BRICS, and APEC.

It is easy to see that not all of these organizations represent the “non-Western” world. By the way, APEC and the WTO include Taiwan. Such a “non-ideological” list shows that in the current conditions of global governance deficit, China does not intend to assume the leadership functions of the only superpower. Beijing is hardly ready to create a system of global governance from scratch, but hopes to stabilize the situation using the existing mechanisms. The breakdown of the system is seen as a “gray rhinoceros. China would consider the complete destruction of the foundations of the world order a catastrophe. All the more so because there are already growing phenomena in the global economy that are extremely undesirable for the growth of the Chinese economy. The congress drew attention to the need to ensure the security of food and energy supplies, as well as to guarantee the smooth functioning of production chains. The most important domestic task was to achieve the country’s technological independence, which will guarantee China’s leadership in the future.

Dangers instead of opportunities

Since the 16th Congress of the CPC in 2002 the Chinese leaders when assessing the international situation said that China was in a period of strategic opportunities. In the early 2000s, it was even named the exact length of time during which the global environment would favor China and its global rise was unlikely to encounter serious resistance. It was believed that for at least twenty years the external environment would carry more opportunities than risks. The very interest in the “gray rhinoceros” concept illustrates a shift in the strategic thinking of the Chinese elite: the focus is no longer on opportunities that need only be skillfully exploited, but on serious dangers that, if not responded to in time, could derail the idea of a great rebirth of the Chinese nation and end the Chinese political system as it now stands.

It is quite possible that the twenty-year deadline could have been extended, but the very idea of a pre-determined, conflict-free world has already begun to clash strongly with reality. The growing social and economic challenges in the wake of the pandemic and the escalating confrontation between China and the United States are accompanied by a general chaoticization of the world system. These trends had to be reflected in the report to the Congress, although the Central Committee report delivered by the Secretary General itself is a document that is extremely abstract. By tradition, it provides a macro view of internal and external problems, rather than proposing a road map.

The resulting formulation looks overly complicated: “a period of a combination of strategic opportunities, risks, and challenges with the growth of uncertain and hard-to-predict factors. But today’s world, standing, as Xi Jinping put it, at a historical crossroads, does not presuppose simplicity.